Articles | My Writing Design

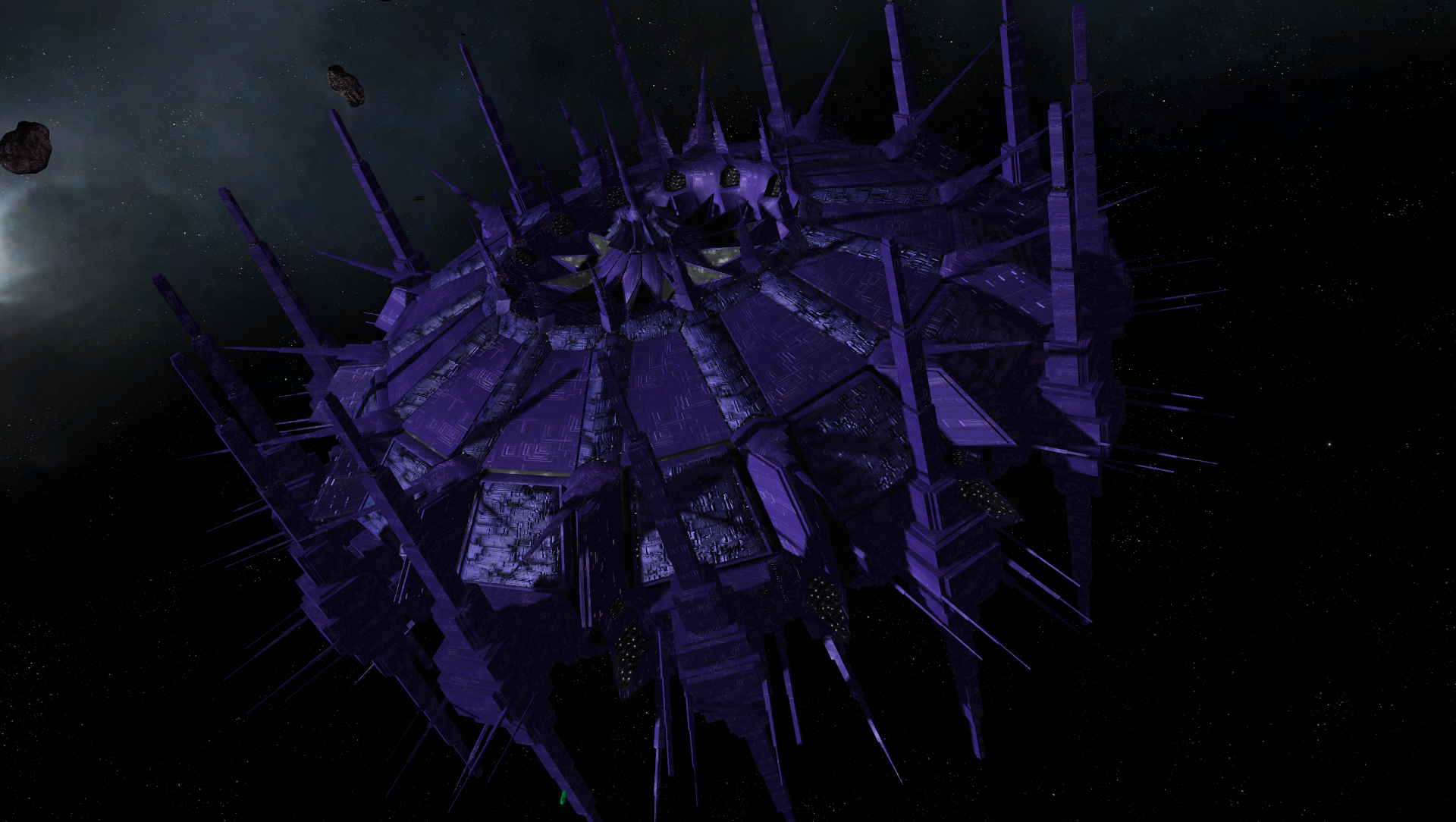

Apex, the world born from a variety of assimilated pet projects and ideas taken from my 2009 and 2010 Starcraft projects Armageddon Onslaught and its attempt in Starcraft 2, epitomizes my value for action-driven setting, personalized storytelling, and symbolism between ideals and personalities tested to their limits in a contest of wits and steel. As an individual focused largely in presentation, I planned to use visuals and audio to guide my hand where narrative could not - as was often going to be the case in Apex's medium, as it was written specifically for games.

Apex had scripts written for both ARPG and RTS concepts, and today I will talk to you about how it was written and why.

The Essence of Design

My written projects are generally worlds of conflict. As is the case with any media you'll find, they are representative of their creators. All things an individual creates - be it a mod, a novel, or a character for a D&D game, are influenced by their own personal values and thus themselves. With this in mind it should be no surprise I focus my attention on action-based media. ARPG's, RTS's, and anime like Fate, Dragonball, JoJo, etc. I live in a world of perpetual conflict - the struggle to survive, the struggle to outwit those out to destroy me, and the struggle to protect the lives of those I care about.

However, I am a very crude and inexpressive person. With having no social contact to speak of, much less with people who share in my interest to create things, I have always focused my efforts on the selfish and the vain. Indeed, my desire to create things inside my head is entirely so I can lose myself in them and forget about the real world. It should be of no surprise to learn, then, that a good amount - at least 50% - of my world's content is derived from things I have seen in my many dreams and nightmares.

Indeed, I dream often. Most of my dreams are terribly unpleasant, though - visions of losing my cats and dogs from the years plague me each and every day. I am constantly waking up to make sure Snowball's eyes are okay - because I had just seen them melting out of their sockets amidst a sea of painful cries. I constantly rush out of bed and onto the floor - I had just seen my dog whom I carried to her death, amongst a half-dozen others, in 2006. The dreams are as real as real can be - moreso, if you consider the fact I live in my head and see the world around me as the imagination.

Amidst the sea of unpleasantness, there are dreams I cling to since years long past and treasure. Amongst them are the myriad of dreams about Throne of Armageddon's worlds - those in which I had lengthy conversations with characters, witnessed great battles, and stood within the shadow of great monuments. I have even played full games of my various mods, or at least what I had hoped the mods would become, within the scope of my dreams. I remember many of them as clear as day, even decades later. I have indeed clinged to those memories, for they are all that is left of me.

There is one constant amidst my dreams, though, and one I have always sought to change - the feeling of extreme loneliness and despair when they end. When I awaken I am immediately reminded that everything I try to do means nothing, and that I am powerless to change my future. This makes positive dreams - like those which gave life to the worlds in my writing - extraordinarily painful, far moreso than nightmares.

What endures from Retribution is not the project itself, but the many dreams I had of things in it, including massive fleet battles with the DyiithJhinn and observing the functions of an Anahn bridge during a jump procedure. They serve as both a window into a better time and an eternal reminder of the colossal failure that Retribution was.

I have always seen writing and other arms of production as a means to bridge the unpleasant - living - between the pleasant - dreaming. The most powerful form of escapism I would be capable of, other than suicide of course, which I've also attempted many times with unfortunate failure. Incidentally, those attempts always came at the beheset of a tremendous failure in a project, such as the death of TOA's writing in 2009.

While dreams have helped build presentation and symbolism for TOA and Apex, the core design of the writing style comes from the emotions and inner dialogue to circulate such symbolism. In that respect, both worlds are heavily centric around conflict, and that conflict is usually, at the heart, driven by conflicts of interest and personality. Indeed, both worlds feature personalities tending to extremes and representing of my own inner voices. Every character I have ever made in any production is a mirror of some portion of myself, because I have always felt confident I can write my own voice without fail. For this reason I cannot do impersations or write other people's worlds/characters as well - they are not my voice, and my response to their inner queries on how to speak or act is no longer something I can process with confidence.

Planning

I don't plan my content. I plan the orchestration of my content. The same goes for my mods and other such projects. Retribution's audiobook is the closest thing I've ever done to scheduling or planning out a project, and even then it amounted to just a bunch of dialogue to voice out and 1-2 lines of notes I took every few paragraphs to help me remember ideas. Most sequences, such as the Execution sequence, the Khoran chargeup, and all of the battles were composited on the fly with no guidelines besides what I "felt" were good directions to move in.

I don't work well on planning because I find I always have a better idea when it comes to actuation. Instead, I plan ahead to give myself the tools to make that actuation happen. For Starcraft, that's assembling assets like graphics and sounds. I always find actually putting that stuff together gives me limitless ideas on how to actually make better use of it, so I really don't plan. I wrote out a lot of mechanical ideas for Apex and Apex's D&D iteration, Starsworn, knowing full well that when the time came to actually build this stuff I'd just throw 99% of it out and do whatever the fuck on the spot. This process isn't planning to me, either, it's just scribbing out ideas in case I might find something amidst them I can recycle in some manner. In that respect tossing out entire projects because some specific thing doesn't work is extremely common for me, and not something that in itself draws my ire. The unfortunate thing is the lack of programming and reverse engineering skills is usually the keystone of failure in projects like Apex's, which relied on features, like a functional computer AI, that aren't available in games like Starcraft without end-user intervention. Therefore the process of tossing projects is generally associated with the process of facing my own incompetence as a designer, and this is what makes the process bitter. Else, I see the process of grinding down ideas, discarding them and salvaging only the tiniest pieces to form the next, as a simple matter of quality control - a process that cannot be planned for.

In fact, I find the entire process of planning out a project before actually working on it idiotic. It's good to have a solid idea of where you want to end up, but most projects who plan ahead never live to see that energy amount to anything. It is always best to act on energy on the spot and make movement towards goals with simple discipline guiding your hand. Planning comes into action only when you set up your environment and tools. In terms of script writing and world building I devote much of my early energy into the very end of the project's concept - the conclusion I wish it to attain. I determine where I want to end up, then find a satisfactory beginning. The beginning is always the hardest part, and for Apex and TOA both this particular part took a great deal of time to really hammer down. Much of the meat of the content thereafter - the journey, so to speak - is best left to improvisation. Ideas form through interaction with the creative process, and those ideas formulate into their own concepts that tend to take life on their own. I will follow them to where they seem to "want" to go, especially with dialogue, focusing on what feels like natural progression, even if it seems to defy my end goal. Often times I am able to make both meet each other in ways even I hadn't expected, which can shape the world in ways I never could have foreseen.

Such freeform mutation can often give rise to exposition and fill creep, so I take many swings at the same content, revising countless times, until I feel like I have chiselled out the majority of excess America. For Apex in this process took around 2 years, but TOA was a decade into the writing of its primary novel and I still felt like I needed to restart the entire thing from the ground up - something I had already done a half-dozen times by then. This is not an uncommon curse that afflicts those with productive aspirations, and it isn't one you should necessarily give into. There are limits to the benefits of discarding old work in favor of new ideas, and finding the boundary between diminishing returns and actual objective polishing is a critical step to becoming a competent designer. If something holds me up for a long time I tend to leave it until I have addressed surrounding components more critically, especially components I feel more confident about, and then ask myself why I feel confident about those and how I can use that confidence to give new life to a troublesome location nearby.

Performance anxiety is a demon that tends to pressure one into leaning into planning, for the belief that a bucket of excel sheets filled with formulas is the key to success is one that is generally held by the cold grips of projects whom died young. I have always, and will always, recommend developers to find an idea they like and then simply attempt it and bullshit it as they go. Often times they will find the idea really wasn't that great, and all of the effort they would have wasted planning for it instead went into developing critical skills, experience, and understanding why that idea didn't work out for them. Such reflection is necessary to make use of preparation to begin with - minimizing energy spent outside of active development should always be your goal, which is why proper tool development is such a critical deal for media. Writing is no different - the tools you are developing are your mental tools, the manners in which you conjure and manipulate information. I found my lack of descriptive skills extremely inhibiting, and no amount of planning or foresight could get me out of this problem. It ultimately drove me to cease writing altogether - but I still make use of what I learned from the struggle to assess third party efforts.

Conflict Resolution

I treat the design process with an even stricter eye than the review process. Apex struggled for years to find a specific sweet spot for the beginning chapters and that is why it was continually torn apart and reconstructed. Refinement came to me elsewhere in the writing as I continued, but particularly the beginning was the part that always failed to catch me as being a compliment to the rest of the project. I despise filler, and the concept of "building up" to the grander parts of the world always came off as convoluted to me. I wanted to initiate players directly into the meat of the writing as fast as possible, but couldn't figure out a way to do so without overwhelming them.

Eventually, I had two separate game arcs in the exact same world - the Apex Primary, which was Alkhazir's arc (seen in Segment 0), and Lazarus' arc, known formally as Apex F. These two forks came out of the same primary story concept - they are the children of the most difficult conflict of them all.

When you have two really great ideas and can't decide between either of them, you may find yourself amidst a crossroads that has no clear resolution. Both Alkhazir and Lazarus made for excellent player characters because both were associated with elements that helped introduce different parts of the world in a manner that made the otherwise overwhelming amount of information much more malleable. The critical aspect behind either character was their role in delivering that information - Lazarus was a studious Warlock whom is broken into recent events primarily by a string of relevant characters, and Alkhazir is a character whom has lost his memory and recovers it as he's pulled through events in Adam's Realm. Both have excellent starting points for unfamiliar players, both have excellent arcs that bring them into the world's primary content immediately, and both are unique and well-developed enough characters to carry the majority of the project presentation single-handedly.

Ultimately, rather than exchange one for the other, I merely rearranged how my presentation was set up so I could use both. I decided I would use Alkhazir to introduce the first parts of the project and then Lazarus later parts. It is uncommon for me to transition character perspectives in such a way, but because I was planning to use this content for a game I didn't see much reason not to take advantage of their unique abilities and perspectives. Later on, as I developed Apex, I was able to cement these characters and their roles primarily through dialogue.

Dialogue-Driven Design

The triple-D's hang heavy in the backdrop of my failure to write Throne of Armageddon. As someone who struggled immensely with descriptive writing, I had come to lean exclusively on my sole strength - dialogue. As I mentioned earlier, I tend to allow things to move naturally in dialogue and I simply let the flow of dialogue design the world for me. Each character has a set of goals and values, and these goals and values are played out like one would naturally expect them to. Of course, there's going to be major gaps in my ability to write accurate dialogue in some circumstances. For example, I've never experienced romance or academia, so writing out those subjects is extraordinarily uncomfortable if not outright impossible for me. Some social situations even outside of those niches can be extremely hard to figure out natural-feeling responses to, which tends to rack up hours in mental soap operas visualizing various paths to choose from. If I don't think I have the experience to write out something I will simply find a way not to. Better to not do something at all than do a half-assed job of it.

If I feel something is holding the project back I tend to cut it without hesitation. I have no patience for wasted time and energy, and will drop enormous chunks of a written work if it feels like I stand to gain from its removal. Apex saw over half of its factions and related characters axed from Alkhazir's arc exclusively because I knew I would struggle to make their assets in Starcraft 2, and they weren't critical to his own presentation. By narrowing my focus I was able to pieces from their remains and use those pieces to strengthen the surviving elements - story hooks, dialogue moments, and character values.

Both Apex and TOA are focused heavily on the motives and interactions of individuals. Retribution's primary arc can be zeroed into just a handful of individuals - Haktish, Adashim, Annashim, the Fear, Mal`Ash, and Adjak. Much of Apex's first segment can be narrowed onto Alkhazir, the Shogun, Larry and Acromagnus. The movement of components around these faces, such as world elements and factions, are seen as bodies of fluid that change shape according to the whims of those faces. They give body and impact to the choices each of these individual makes. Thus, dialogue is seen as the single most major world building tool in any project be it a game or a novel.

One of my core game design philosophies is to never interrupt gameplay. Apex was designed to never once take control away from the player or prompt them with a cinematic during the length of a mission. Only inbetween missions would cinematics be played. Therefore, anything that needed to be done for the story during a mission would be done exclusively through player interaction and ingame dialogue. No hints or objectives would be introduced through popups or other out-of-character elements - in-character dialogue was the sole method I would use to bring important information to the player.

All that said, I go through the effort to justify every single action at the lowest technical level. If someone nothin' personnel kid's another someone, there should be a very logical and low-level reason why that can happen. The psionics and elements system in Throne of Armageddon took over a decade to hammer out even remotely reasonable details for, which was the primary component I ended up prying from its corpse and refurbishing for Apex. Indeed, the technical systems of the worlds are seen as dialogue all on their own - they are a dialogue between me and the foundations of the elements of my world that give life to my characters. If something is difficult to be believed, inconsistent with other content, or otherwise fantastical by the limitations of its own setting, it lacks value and impact. Thus, to give the actions of my characters and their decisions the greatest impact I ensure that the realworld components surrounding them are as logically sound in reality as possible even if we're talking about a world with that has something like spirits in it.

The second a world starts becoming inconsistent with itself it pulls everything ever presented into question, which challenges the design of all characters and dialogue and destroys the suspense of belief in their individual projections. Inconsistency in technical elements is just as bad as inconsistency in character personality, because the world itself has its own personality - and the characters as personalities are extensions of that world and vis versa. At every corner must they be consistent with one another, and the only way to ensure this is to build low-level components for every thing you pull out of your ass, be it magic, gods, or somewhere inbetween. These technical elements need not ever expose themselves to the player but they keep you, the designer, honest with your own work and ensure you won't be scratching your head as the content piles up and you need to start asking yourself questions about certain interactions. Even something as simple as the reasoning why the Holy Hell Hope Sword is necessary to defeat the Big Bad Dragon is necessary, because else players and readers both will be tearing apart unsound logic surrounding their character's motives to involve themselves with it.

A game world is no different from real life - people ask questions about every detail, and it's your responsibility to have answers for them. You can't plan every answer ahead, nor you should try to, but you should have designed your world in a way in which you have the mental tools to formulate sound reasoning to formulate those answers from. Therefore your characters need not adhere to unrealistic projections to sidestep laziness in design and you don't ever have to worry about being uncomfortable with your own world. This also lets you avoid Metzen syndromes and having to retcon half of your setting every few paragraphs.